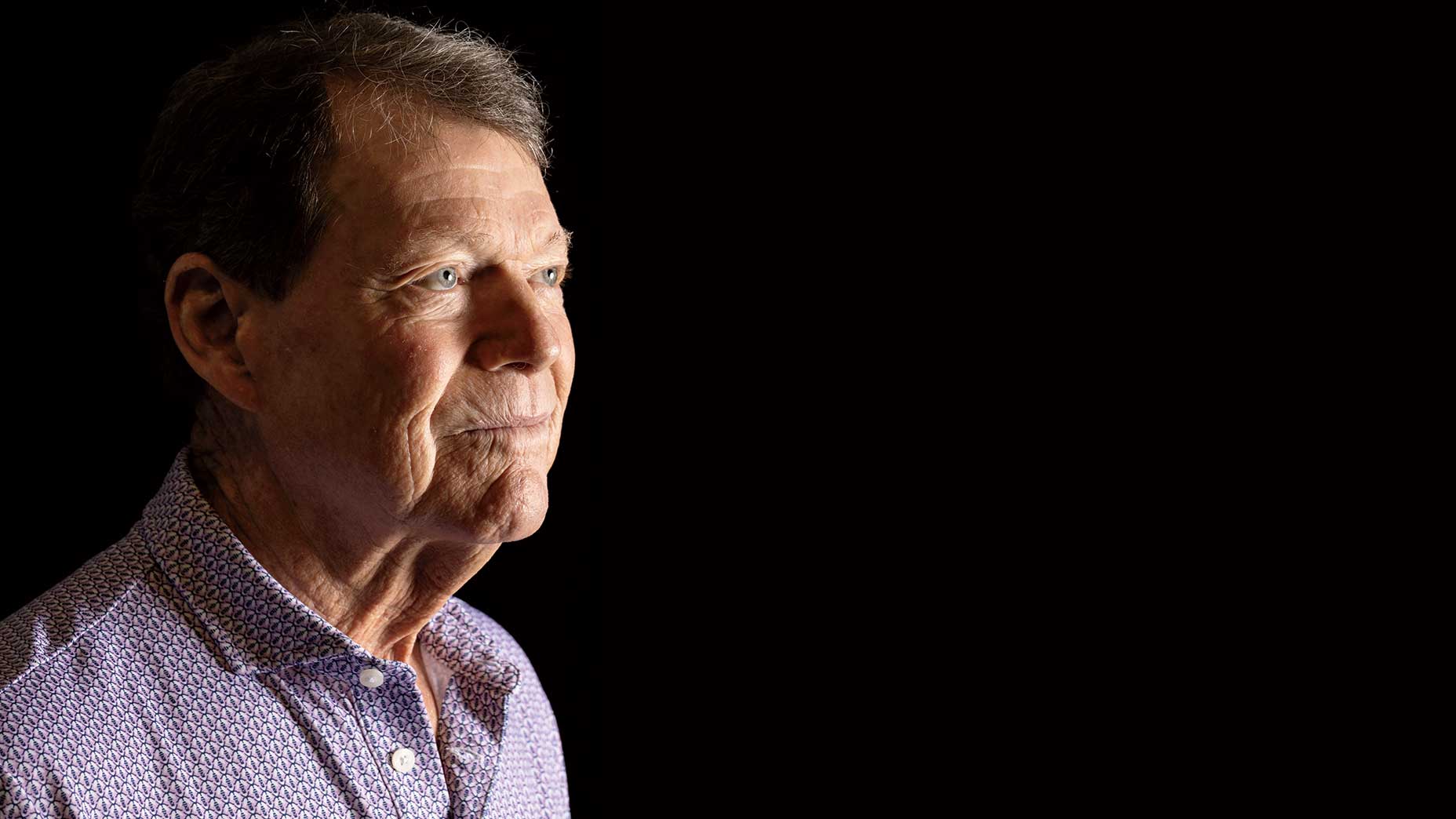

How triumph at Royal Troon changed a life (and legacy) 51 years ago

Tom Weiskopf's crowning achievement as a player came at the 1973 Open.

Getty Images / R&A

“I’ll never consider myself a great player until I win a major championship,” said Tom Weiskopf before play began in the 1973 Open Championship on Scotland’s southwest coast, at Royal Troon. And if that were ever going to happen, it seemed likely the week commencing July 9, 1973, would be the time, and the dunescape, which at points is unexpectedly dotted with palm trees along the Firth of Clyde, would be the place.

It was an era that remains unmatched in golf history for the sheer magnitude and array of legendary competitors and playing styles. Just the month before, Johnny Miller stepped on the first tee in the final round of the U.S. Open at Oakmont, a full hour ahead of the final group. He shot 63 and tore past Jack Nicklaus, Lee Trevino, Gary Player and Arnold Palmer to win.

Miller’s barrage of birdies also saw him pass Weiskopf, who finished third at Oakmont — his fifth top 10 in a major championship. Weiskopf had been on his own spree of superb play at the time, winning three PGA Tour events in the two months leading up to the Open at Troon.

It had been a long journey for Weiskopf, who joined the Tour in 1965, when Nicklaus was at his peak. Weiskopf was one in a parade of players burdened with the millstone of being the Next Nicklaus. At six-three, he towered over the real Nicklaus and had the added burden of being from the same state (Ohio) and of attending the same university (Ohio State).

Weiskopf ’s graceful and regal swing was envied, and few in the era could match his length and accuracy when he unsheathed the driver. Those unfamiliar with Weiskopf as a player might compare him to Greg Norman, a Next Nicklaus of the subsequent generation who also pounded out long, straight tee shots and, like Weiskopf, had an unfortunate knack for coming up short in some of the game’s most dramatic moments.

Weiskopf, who last month was posthumously inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame, wasn’t a next anyone, however. He was all Tom Weiskopf, and that included a perceived fury that, in reality, was frustration that showed when he didn’t achieve perfection on the golf course. He was sometimes called the Towering Inferno, a nod to a disaster film of the era.

“Tom was a perfectionist, often to his detriment,” said his wife, Laurie, during a recent chat. “He was like that off the course too. When something was important to him, he’d be up in the middle of the night trying to figure it out. He wouldn’t let it go until he solved it.”

On a misty Saturday at Troon 51 years ago, Tom Weiskopf might not have achieved perfection, but he did find peace.

“POTENTIALLY, HE’S BEEN AN AWFUL good player for an awful long time,” said Jack Nicklaus of Weiskopf that week at Troon. Weiskopf came out of the gate with 68 on the Open’s Wednesday start and followed with 67 on Thursday. From his perch atop the leaderboard, Weiskopf could see Miller three back and Nicklaus four back. Miller inched closer on Friday, and in the Saturday finish, British veteran Neil Coles (a brilliant player largely unknown to fans in the U.S. due to his fear of flying) posted 66 and Nicklaus reached for the Claret Jug with 65.

Excitement crackled through the crowd as Nicklaus made his move and throaty cheers urged on the home hero, Coles. In the end, it was Miller who had the best crack at Weiskopf. There was a moment when unmet self-expectations could have disrupted the moment for Weiskopf, when perfection not achieved could have led to self-destruction. At the par-4 13th hole, he missed the green by 40 yards — a poor shot for any pro — and followed with another weak play. A 15-footer for par looked scornfully at the hole, and Miller was within two. But Weiskopf showed no outward signs of disappointment in himself. At the 15th, Miller was standing over a three-footer when the scoreboard posted that Coles had reached nine under for the tournament. Amidst the crowd’s reaction, Miller backed off, then missed the putt. Weiskopf was in the clear and won with 276, tying Arnold Palmer’s Open record in the process.

“I was in complete control of myself,” Weiskopf said afterward. “I was never really worried. Not that I don’t respect the ability of Johnny, or Jack, or Neil. I just knew that no matter what happened, I was going to win.”

Later in life, Weiskopf said that he was inspired at Troon by the passing of his father earlier that year: “My dad died in March. I kind of felt like I had let him down. He had given me so much. I would talk to him occasionally on the course that summer, after he was gone, when things weren’t going well.”

IN THE PRE-TEAM EUROPE DAYS of the Ryder Cup, when the outcome was seldom in doubt, Weiskopf once skipped the event to go sheep hunting in the Yukon. It was a long-planned trip and Weiskopf informed the PGA of America of his intentions well prior. His decision caused a bit of a kerfuffle that was exacerbated by some miscommunication, but the story is related here to help make the point that Weiskopf did not live his life to play golf — rather, golf was just part of his life.

“Professional golf was not Tom’s life,” says Laurie Weiskopf. “It’s what he did for work. It was a lot different than how Jack looked at his life and career. Tom had other things he wanted to do, things that were as important to him. Professional golf was a job. Golf course architecture was a different story — that was his love.”

More Weiskopf

It is fitting then, that Tom Weiskopf’s most lasting impact on the game may not be his tenure as one of the world’s best players — a contemporary of titans — but rather as creator of golf courses to be enjoyed by people who also lead lives not centered around professional golf.

“A lot of player-architects are inclined to design courses that suit their own games and don’t see the perspective of the everyday golfer,” says Phil Smith, Weiskopf’s longtime collaborator as a course architect. “It’s a hard game to start with, and he wanted to make sure people had fun playing. That was his design philosophy: Give players several different options to play a hole. You can always toughen up a course by bringing the rough in. He would bunker one side of the fairway but not both. If you bunker both, you make it more difficult for people trying to have fun, and you limit what you can do to toughen up the hole.”

An argument can be made that Weiskopf — who is credited with more than 70 designs or codesigns — returned a bit of sanity and a lot of joy to the game at a time when course design had turned into a bit of an arms race to see who could build the hardest, longest, most impossible track to play. It was Weiskopf who emphasized, and some would say reintroduced, drivable par 4s, with all the strategy, drama, options and risk-reward they offer to players of every skill level. None more so than the 17th at TPC Scottsdale, a Weiskopf–Jay Morrish design collaboration that stands the test every year at the Phoenix Open and for 51 other weeks of the year is a blast for all who play it.

“Tom made drivable par 4s an integral part of every course we did,” says Smith. “It’s tougher than it looks to design a good, reachable par 4. He was so good at understanding you had to give a player a challenge off the tee and see the risk they’d be taking. He was very good at creating perceptive illusions, where you weren’t sure if a bunker was up against a green, for example.”

Smith fondly recalls their first trip to the site of Castiglion del Bosco, a 2012 course he and Weiskopf created in Tuscany.

“On the drive there from Rome, our necks were killing us because we kept pointing and saying, ‘There’s a good spot for a golf course’ and ‘There’s another good spot and another one’ and so on. We understood the history of Tuscany enough that we didn’t want to hurt your eye. It just painted itself into the landscape. We didn’t use a strong white sand, for example; we kept it earthy.”

Over the past year and a half, Smith has been working on restoring the bunkers to the original design of the course, which hosts the annual Tom Weiskopf Invitational, a member-guest of sorts, again befitting a man who was about more than fame and glory on the course.

“Tom wasn’t always recognized in public, but when he was it was a compliment to him,” says Smith. “He was always great with fans. I would never want to be famous, but he was the perfect kind of famous.”

When Tom Weiskopf died in August 2022 in Big Sky, Montana, “he was very happy, pleased with his life, very content,” his wife, Laurie, remembers. “That was awesome to see. Most people never feel that.”